This is THE question, isn’t it? I think a lot of people, myself included, just start with a formula they find somewhere but don’t take the time to test it against other options. The good news is, I’ve done a test for you. I’ve done a mordant strength test with aluminum acetate previously; this is a mordant strength test with potassium aluminum sulfate, aka, alum mordant for protein fibers.

My underlying question in doing this experiment is how best to handle wool, alpaca and silk blend roving— how much heat, agitation, time and mordant gives the best result? And do I need to use cream of tartar (potassium bitartrate)? My preferred outcome will be good color uptake while still having a nice hand and easy spinability.

The first recipe I came across was from John and Margaret Cannon in Dye Plants and dyeing, which uses 18% WOF alum and 6% WOF cream of tartar. I started using it and had good results, but in my natural dye class we use 10-15% alum with no cream of tartar. I usually bring my mordant bath up to temperature (about 160-170F), turn off the heat, and let my fiber sit overnight. In class (where we generally use fabric samples, not yarn or roving) the fiber is at constant temperature for an hour (170F or so— not boiling, but steam coming off the water) and then removed and rinsed. The least amount of alum mordant I’ve seen used is from Jenny Dean, just 8%, but with 6% cream of tartar.

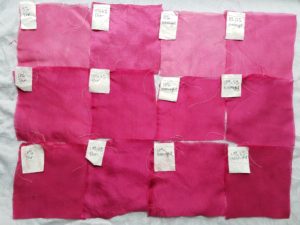

This experiment is my fairly best comparison of apples to apples to apples, starting at the low end of 8% alum, ending at the high end of 18%, and splitting the difference at 13%. All mordant strengths are tested with and without cream of tartar, and processed at heat (170F) for one hour, or brought up to heat and then turned off and let sit overnight, for a total of 12 different samples. Both wool, silk, wool/silk blends and a silk/plant fiber blend were sampled, in the form of fabric and also commercially prepared organic undyed yarn. All samples of the same mordant bath were processed together, and all samples were wetted out for at least an hour. In the end, ALL of the samples went into the SAME dyepot of 20% WOF cochineal, a good strong dyepot, with the hopes of disambiguation.

There were some interesting results!

Even before I mordanted anything, the visual difference between the alum with/alum without cream of tartar bath was obvious. With cream of tarar, the bath was clear. Without, it had a cloudy, milky look. This persisted after the fiber was removed from the mordant bath. The ph of each bath remained the same, about 3-4.

After I’d mordanted my samples, but before I’d dyed anything, I tested the hand, or feel, of all my samples— the common complaint about increased alum strength is that is can make the fibers feel “sticky”. With all of my wool samples, regardless of alum%, those without the cream of tartar felt coarser. The yarn especially felt sticky without cream of tartar. On the silk noil samples, the samples WITH cream of tartar at 8% mordant strength had a more noticeable yellow cast . The hand of the silk noil and habotai were not discernibly different, but the silk-faced plant blend and the wool/silk were definitely smoother/nicer with the 6% cream of tartar.

So what about the color? Take a look! These samples are all laid out in a 4×3 grid as follows:

8% 1hr, 8%/6% cream of tartar 1hr, 8% overnight, 8%/6% overnight

13% 1hr, 13%/6% 1hr, 13% overnight, 13%/6% overnight

18% 1hr, 18%/6% 1hr, 18% overnight, 18%/6% overnight

Silk habotai. The cream of tartar definitely helps the dye uptake, especially noticeable at the lowest strength mordant.

Silk noil. The unevenness of color I attribute to not enough wetting out time. In the future anything with silk will soak overnight.

This is a thin 60%silk/40% wool twill. I was surprised that I liked the 18%/6% 1hr mordant the best.

Medium weight wool challis. Not as great a difference between the 13% and 18% mordant strengths as on the silks.

Commercially prepared undyed organic merino yarn. I didn’t scour it, and I should have! I think the color uptake at all mordant strengths would have been much better. The 18% overnight skein is missing— I ran out of yarn.

Takeaways:

Its pretty clear that more mordant equals more dye uptake. This was a strong dyebath, with plenty of color left over (I dyed several more yards of fabric afterwards with the leftover bath). Between 13% and 18% the difference isn’t as stark as at 8%, so I might do an additional test at 15%WOF and see if I can see a big enough difference to merit the additional mordant.

It’s not so clear in the photos, but the samples mordanted on heat for one hour had a nicer, more even color than the ones brought up to temperature and then left to cool overnight. This surprised me. In the future I will probably keep on heat for one hour, then let cool naturally before removing the fiber. This has also dissuaded me from trying a recipe I found on the internet for mordanting in cold water!

I will definitely be wettting out silks overnight, and scour any fiber I haven’t already prepped myself. I will use cream of tartar, for both mordant uptake and nicer hand. The final test, of course, is a light-fast test. My hypothesis is that the higher mordant strength will be more fast.

At this point I’m of the opinion that the prep work, from scouring through mordanting, is the key to nicely dyed fiber. The dye bath is basically proving how good a job I’ve done. A stronger dye bath won’t produce any more color than the amount of mordant bonded to the fiber. This test was done with cochineal, which won’t dye without some sort of mordant; if I was dyeing with something substantive like onion skin, the extra mordant strength may be unnecessary.

I hope this helps answer the question of how much mordant *you* really need: by all means, do your own experiments!