Spindle spinning is cool. There are loads of devoted spindle spinners out there and those of us who favour our wheels are missing out. What do they know that we don’t?

Picking up a long thread

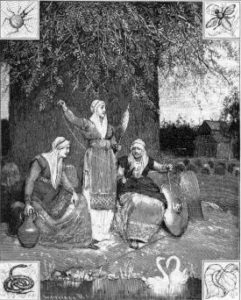

Humans have used spindles–and even simpler sticks–to spin fiber into yarn for thousands of years. For me, using a spindle is a bit like time travelling with yarn. When I pick up my spindle I’m doing something very similar to our ancestors. That’s a powerful thing, literally picking up the thread begun by people who lived in a world completely different to mine. It’s a point of commonality–making threads to weave and clothe ourselves.

Imagine how much work went into making garments before that process became industrialised. Clothing was something people held onto and mended. The idea of clothing shops, let alone throw-away fashion would have been unfathomable.

Spindling reminds me of that.

Spindle as a symbol of female power

Archeologists find whorls in excavations all over the world. Some viking women were buried with their spindle whorls (the weight) and weaving tools.

“[T]he presence of gendered goods at Viking controlled territories is a concrete indication of female burials. These gendered goods include “(pairs of) oval brooches, disc brooches, trefoil buckles, arm rings, necklaces, caskets, spindle whorls.” (Women Traders of the Viking Age: An Analysis of Grave Goods)

The spindle and weaving tools was associated with female power in some ancient Northern European traditions.

“According to Norse mythology, aristocratic women were associated with the Norns—the mystical weavers of fate who could spin or cut off the threads of human life and destiny. High status women were, therefore, felt to have an ability to influence fate.” (Ancient Scandinavia: Viking Women)

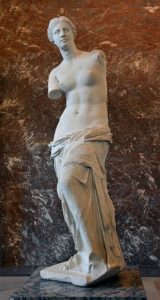

“She had the body of a Venus… with arms”

How is it the dumbest AC/DC lyric reminds me of spinning? Well. You know Venus. She’s the armless statue in Paris’ Louvre Museum. People like to take selfies with her. There are people out there who wonder what the Venus de Milo was doing… when the statue had arms. Some people believe she may have been spinning.

“One idea in particular piqued the interest of Elizabeth Wayland Barber, a professor emeritus at Occidental College who wrote the book Women’s Work: The First 20,000 Years. Perhaps, Barber thought, Venus was spinning thread. Spinning in ancient Greece had associations with fertility and sex — fitting for the goddess of love and reproduction. Women created thread, seemingly from nothing but a bit of fluff, similar to the mystery of birthing babies. Also, women on Greek vases depicted spinning are actually prostitutes occupying themselves as they wait for clients.” (Smithsonian Magazine)

The idea of a spinning Venus de Milo was tested by Virginia Postrel who hired San Diego-based designer and artist Cosmo Wenman to create a 3D model of Venus spinning. She talks about that process in a 2015 Slate article.

The model he made is now in a museum in Switzerland–just in case you want to check it out.

Simplest spinning tool

On a more practical note: spindles come in all shapes and sizes, and they are the simplest spinning tool. You can put twist into yarn using just a stick. I love that you can make your own spindle with a few dollars worth of supplies. I’ve made a spindle out of my childhood Tinkertoys.

It’s simple. It’s easy. It’s accessible. Spindle spinning doesn’t have a financial barrier for entry. You don’t need a niddy noddy, lazy kate or a ball winder. You don’t need accessories. Just spin and make yarn.

You can make any kind of yarn on a spindle–two-ply, three-ply any ply, fancy yarn or not. You don’t need certain types of spindles or to make any adjustments to make different yarns. Also, I as I pointed out a few years back, spindles are perfect for spinning on the go.

Stand and spin

My back has been bothering me recently. Sitting at my wheel can make it worse. I realised another great thing about spindle spinning: standing and spinning. Although after awhile my shoulders do get a little tight. Take breaks.

Spinning on a spindle reminds me that not every project needs to yield tons of yarn. We don’t always have to set out to spin a sweater’s worth. Spindles are perfect for making mini-skeins for small projects.

Many spindle spinners do spin lots of yarn for big projects. Check out the Spindlers Ravelry group and prepare to be impressed. Lots of inspiration.

I’d love to hear from people who like to spindle spin. What is it about this kind of spinning that appeals?